|

|

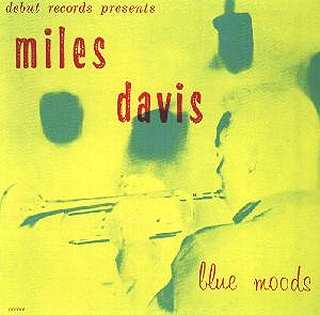

MILES DAVIS - Blue Moods, Prestige

Records, 1955

MILES DAVIS, trumpet; BRITT WOODMAN,

trombone; CHARLES MINGUS, bass; TEDDY CHARLES, vibes; ELVIN

JONES, drums

|

|

|

|

|

|

| NATURE BOY |

THERE'S

NO YOU |

| ALONE

TOGETHER |

EASY

LIVING |

|

|

|

There was a boy . . somehow

strange and enchanted, perhaps . . . but a natural, not a

nature boy. This one grew and learned, among other things, not

to whistle at the lovely lady of a cigar-smoking citizen of

Mississippi. Which made it possible for him to grow enough to

read news service reports about what happens to that kind of

boy. It made possible, too, some disenchanted wanderings, with

horns often not his own; wanderings along a series of personal

precipices where nostrils may ache from the sheer agony of

breathing.

If there is dignity and artistry

in such a boy, he will record such a life with gaunt gestures,

or as an anointed conscience, or as the inveterate cynic, or,

or . . . there are some few, even, who merely reflect, neither

urging nor decrying. Miles, it seems to me, is one of these

latter. His the almost fragile, though never effeminate,

tracing of a story line which is somewhat above and beyond

him, of almost-blown-aside, pensive fragments which are always

persuasively coherent.

His are moods, blue ones if we

can allow for a programatic spectrum. Not the kind of blue

that happens an Mondays those lastNIGHTWASanight,

now-it's-five-days-till-Friday kind of blues. More like Sunday

blue; nothing to do in the morning, no family dinner, only a

movie in the afternoon and a gig at night kind of blues.

That's what Miles says to me anyway, says it in particular and

at length in the course of this LP, says it, too, in as moving

a way as it can be said.

Just about one month before

these tracks were cut, Miles had performed at The Newport Jazz

Festival. Within the ranks of the professional critics, there

was not too much notice taken when he joined the group already

on stage. Professional listeners are blasÚ, especially when

an artist is as unpredictable as Miles; unpredictable, that

is, in terms of the relationship between what he can do and

what he will do. And for many of us there is a forgetting that

the improvising soloist, with muse on the wing, so to speak,

is confronted with so many technical problems, that a

statement of cohesion and beauty is an awe-full happening. Add

to this the failings and weaknesses of all human beings, and

there is no wonder left that we can hear what amounts to raw

genius in one evening, or one set, or, even, one number, and

then, immediately after, discover nearly meaningless

mouthings. It's enough to drive you mad. It has been enough to

drive a number of jazz musicians mad, and to drive more to

madnesses of various sorts.

In any case, on this night at

Newport, Miles was superb, brilliantly absorbing, as if he

were both the moth and the probing, savage light on which an

immolation was to take place. Perhaps that's making it seem

too dramatic, but it's my purely subjective feeling

about the few minutes during which he played. And,

over-dramatic or not, whatever Miles did was provoking enough

to send one major record label executive scurrying about in

search of him after the performance was over. And dramatic

enough to include Miles in all the columns written about the

Festival, as one of few soloists who lived up to critical

expectations. But when you mention it to Miles, he says,

"What're they talking about? I just played the way I

always play."

He doesn't always play that way

of course. Up to, and down to, certain limits, everyone plays

the way he is And Miles is no exception. Then, too, the

presence of Chet Baker on the program, and of Shorty Rogers in

the same country, these two his most successful mutants, might

have produced the kind of tension which professionals can turn

into victories.

So all that happened before this

record date. That, and much more, of course, because Miles'

life has resembled both the moth and the flame during the

twenty-eight years that he has lived it, especially since

1945, when he made his first major public impression while

with Bird at the Three Deuces in New York City. Moth and

flame, too, for the last few months, until just recently, when

the bother and anxiety about a growth in his throat had made

the cat-slight Miles speak and walk in such whispers that his

always present, kind-of-nosethumbing withdrawal seemed nearly

complete. More moods.

It may seem that there is

altogether too much attention being paid to feelings, to

moods, in this essay. After all, like skin, all of us have

moods.

|

|

But there are skins and skins. And some people make

moods work for them. Which, I suppose, could be a beginning in

the definition of an artist. That, while he is perhaps more

sensitive to the synthetics of the world around him, hence

probably more tortured by them, he can fashion his turmoil

into a tale for a purpose as singular as himself.

Lo the pensive Miles. Complete

with moods, he waited one hour in front of his hotel, leaning

detachedly against a fire plug, waiting to be picked up,

apparently never doubting that he would be driven to the

recording studio, which was only two blocks away, as he had

been promised. Then, on the way to the studio, his one major

comment: "I hope I won't have to hit Mingus in the

mouth." This, of course, despite the fact that Mingus

could carry two of Miles around the block in a half-mile

gallop. More in affirmation that he Miles was the boss, was tough,

in that curious use of the word by musicians wherein the top

men in a particular instrument are acknowledged as leaders in

other sections of life as well. (Thus, Max Roach, the

toughest of drummers, has, and will again, make

pronouncements about such things as the disposition of funds

from a benefit for another musician, and his pronouncement

will carry immense weight whether or not he is any authority

on the subject.)

Once in the studio, where Mingus

was bothering the drummer -- all bass players bother drummers

and vice versa -- it seems part of the nature of things --

Miles moved quietly into a corner and waited. Four other moods

waited to be served: Teddy Charles, hurriedly writing

arrangements (he did all but Alone Together), ordering

himself a light lunch ("three ham and cheese and some

beer"); trombonist Britt Woodman, who taught Mingus how

to box, fussed with his slide; Elvin kept adjusting his foot

pedal; and Mingus, blithe spirit, alternately fussed and fumed

like a great rooster in attendance to a hatching.

All those moods, present and to

be accounted for in the music on this LP. For example, you

don't hear it here, but on one take Miles wandered so far

afield that he was completely lost. But he made no mention of

it, not even a request for another take, although,

fortunately, another was made, almost as if he really didn't

care, was above caring, whether anyone had discovered the

error.

And the tunes: Nature Boy,

and where was I; Alone Together, oh there I am; There's

No You, there never was; and Easy Living, maybe,

but I haven't seen it. All cut of the some cloth. Again,

moods. Again, blue.

From this, and the sensitivity

of each musician to the others, comes a clarity of expression

which makes annotation superfluous, perhaps, even

presumptious. But there are these things which occured to me,

which may make this seemingly strange sales-talk more

persuasive. (Sales-talk it is, too, for I am moved enough by

this poignant side of jazz to boost its circulation.)

If Duke Ellington would listen

to There's No You, which event I very much doubt, he

would find some incentive for writing again. Because here

Ellington trombonist Britt Woodman plays with an eloquence

which has to preclude the further use that Duke makes of him

as a Lawrence Brown voice. Here, too, as on the other two

arrangements of Teddy's, is the clever anticipation, in

written lines, of what Miles will express, as well as Teddy's

beautiful solo. AND MINGUS.

And, Mingus again on Easy

Living, dig especially his support of Miles, and, then,

Miles' re-entry above the ensemble during the final chorus. Alone

Together, which Mingus arranged, is typically his -- the

throbbing of collected hearts, all about a two-headed title.

Here, again, his backing is superb. Through it all none of the

musicians show Miles' finality of mood, but they do perfectly

match him as if they shared the same secret, each one adding,

as is natural, his own interpretation, and, in the case of

Teddy and Mingus, his own answer to that secret. In that very

special way it is Miles' album in the some way that a wedding

always belongs to the bride no matter what entertainment is

presented at the reception.

These are reflections about a

life in which we are all shareholders.

BILL COSS, Editor, Metronome

|

|

|

|

This recording was cut at 160

lines per inch (instead of the usual 210 to 260 lines per

inch) making the grooves wider and deeper and allowing for

more area between the grooves for recording the bass

frequencies. This allows for a wider excursion of the needle,

giving more level and more bass than on the usual LP and was

deemed necessary to reproduce the extended bass range and give

the listener more quality to that of high fidelity tape

recording.

|

|

| DEB - 120 |

33 1-3 RPM |

99% Reproduction of Hi-Fi Tape

Sound |

|

![]()